Dickens' A Christmas Carol - "A Ghost Story of Christmas"

The Citizens Theatre's production of A Christmas Carol opens Sat 29 Nov, capturing the inventive, heart-warming and spine-tingling spirit of Dickens' original novella. Assistant Director Stephen Darcy explores the history and impact of this most enduring of Victorian tales.

Have you ever heard of 'A Christmas Carol'? A book about a mean old man visited by ghosts? Why is such a story both so well known and so popular?

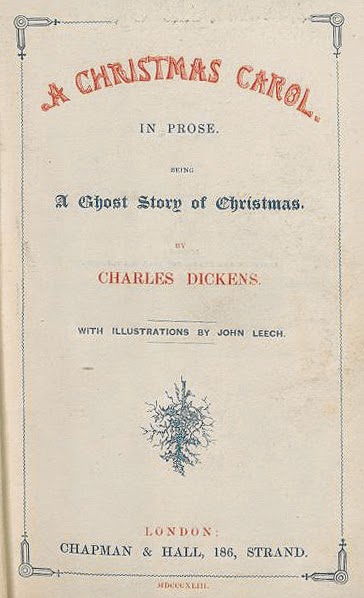

Charles Dickens wrote 'A Christmas Carol' rapidly in October and November 1843 and it was an instant hit. The book sold over 6000 copies in the first few days of sales alone. This may have been helped by the fact that Dickens set the price at five shillings so that the book was affordable to nearly everyone. He paid for the production costs himself, giving the book a lavish design which included a gold-stamped cover and four hand coloured etchings (see below). The Christmas Carol was pirated almost immediately and Dickens was forced to spend a lot of money on court proceedings. Although he won the case, he lost a fortune as the rogue publisher declared bankruptcy leaving him with a bill for the full legal costs. So in spite of the instant and enduring popularity of the story, it resulted in very little profit for Mr. Dickens.

A suggested source for this much loved classic would seem to be the Christmas Chapter of the Pickwick Papers (December 1836) in which the protagonist Gabriel Grub, a misanthropic, curmudgeonly bachelor is visited by the goblin king and his smiling courtiers. They serve to reintegrate Grub socially and restore him to a state of charity with the rest of humanity. The parallels to Ebenezer Scrooge are clear. Another inspiration for this most loved Christmas story is a true family reunion. Dickens was invited to speak at the first annual general meeting of the Manchester Athenaeum, an adult education institute for the working class. Sharing the speakers’ platform with future Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, Dickens, in his address, alluded to the Ragged Schools, self-help institutions for the urban poor which he was encouraging wealthy friends to support. While in Manchester, he stayed with his beloved older sister, Fan, one of whose two young sons was a frail cripple. This boy, no doubt the inspiration for Tiny Tim, died early in 1849 following the death of his mother some months before. Dickens understood poverty. He and his family were frequently very poor. This happy visit with his sister (no doubt the Little Fan of the book), combined with his knowledge of urban poverty and hardship, provided a strong inspiration for 'A Christmas Carol'.

So popular was 'A Christmas Carol' that it became central to Britain returning to the idea of Christmas as an important part of the calendar. By the early 1800’s the mid-winter break had fallen out of favour. The romantic revival of Christmas traditions began to thrive again with German Prince Albert’s marriage to Victoria. German customs such as decorating a Christmas tree arrived and singing carols became popular once again. The first Christmas card appeared in the 1840’s. Dickens tale of Christmas cheer rekindled the joy of Christmas in Britain (and also in America where he enjoyed a huge following) and the story is still relevant today. It sends a message that cuts through the materialistic trappings of the season and gets to the heart of the holiday. Dickens describes Christmas as, “a good time: a kind forgiving, charitable, pleasant time: the only time I know of in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of others below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys”. For the rest of his life Dickens described this as the “Carol Philosophy.”

There can hardly be a more resounding compliment to Charles Dickens’ creation than that which came from rival novelist William Thackeray who described the book as “a national benefit, and to every man or woman who reads it, a personal kindness.” Writing about Tiny Tim, Thackeray added, “There is not a reader in England but that little creature will be a bond of union between the author and him; and he will say of Charles Dickens, ‘God Bless Him!’ What a feeling this is for a writer to inspire, and what a reward to reap!” That is praise indeed and all the more so from a fellow writer.

Not long after it was published, Dickens embarked on full readings of this favourite short novel. These readings were hugely popular and became an important revenue stream for him. Without a single prop of bit of costume Dickens peopled his stage with a throng of wonderful, colourful characters. On performance days he stuck to an unusual routine. For breakfast he had two tablespoons of rum flavoured with fresh cream. For tea a half pint of champagne and half an hour before the performance he would drink a raw egg beaten into a tumbler of sherry. During the five-minute interval, he invariably consumed a quick cup of beef tea, and always retired to bed with a bowl of soup. This unusual pre-performance ritual must have contained some alchemic quality because his readings were always incredibly popular and well received. His last such reading took place at the St. James Hall in London on March 15, 1870. At the end of the performance, he told his audience: “From these garish lights, I vanish now for evermore, with a heartfelt, grateful, respectful and affectionate farewell.” With tears streaming down his face, Dickens raised his hands to his lips in an affectionate kiss and departed from the platform for the final time. He died three months later, aged 58. Dickens name became so synonymous with Christmas that on hearing of his death a little girl asked, “Mr. Dickens dead? Then will Father Christmas die too.” Happily, the tale of Scrooge is so endearing and enduring that in spite of Dickens’ own mortality, Christmas certainly did not die, nor did his much loved A Christmas Carol.

Image Reference: the Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham. http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/news/latest/2012/12/christmas-carol-images.aspx

|

| Title page of the 1843 first edition. From the Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham |

Have you ever heard of 'A Christmas Carol'? A book about a mean old man visited by ghosts? Why is such a story both so well known and so popular?

|

| Cover of the first edition of A Christmas Carol, 1843. Dickens paid for the printing costs himself, but set the price low at only five shillings |

A suggested source for this much loved classic would seem to be the Christmas Chapter of the Pickwick Papers (December 1836) in which the protagonist Gabriel Grub, a misanthropic, curmudgeonly bachelor is visited by the goblin king and his smiling courtiers. They serve to reintegrate Grub socially and restore him to a state of charity with the rest of humanity. The parallels to Ebenezer Scrooge are clear. Another inspiration for this most loved Christmas story is a true family reunion. Dickens was invited to speak at the first annual general meeting of the Manchester Athenaeum, an adult education institute for the working class. Sharing the speakers’ platform with future Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, Dickens, in his address, alluded to the Ragged Schools, self-help institutions for the urban poor which he was encouraging wealthy friends to support. While in Manchester, he stayed with his beloved older sister, Fan, one of whose two young sons was a frail cripple. This boy, no doubt the inspiration for Tiny Tim, died early in 1849 following the death of his mother some months before. Dickens understood poverty. He and his family were frequently very poor. This happy visit with his sister (no doubt the Little Fan of the book), combined with his knowledge of urban poverty and hardship, provided a strong inspiration for 'A Christmas Carol'.

|

| "Scrooge and Marley's Ghost", hand painted illustration by John Leech, 1843 Chapman & Hall 1st edition. From the Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham |

So popular was 'A Christmas Carol' that it became central to Britain returning to the idea of Christmas as an important part of the calendar. By the early 1800’s the mid-winter break had fallen out of favour. The romantic revival of Christmas traditions began to thrive again with German Prince Albert’s marriage to Victoria. German customs such as decorating a Christmas tree arrived and singing carols became popular once again. The first Christmas card appeared in the 1840’s. Dickens tale of Christmas cheer rekindled the joy of Christmas in Britain (and also in America where he enjoyed a huge following) and the story is still relevant today. It sends a message that cuts through the materialistic trappings of the season and gets to the heart of the holiday. Dickens describes Christmas as, “a good time: a kind forgiving, charitable, pleasant time: the only time I know of in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of others below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys”. For the rest of his life Dickens described this as the “Carol Philosophy.”

|

| "Third Visitor", hand painted illustration by John Leech, 1843 Chapman & Hall 1st edition. From the Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham |

There can hardly be a more resounding compliment to Charles Dickens’ creation than that which came from rival novelist William Thackeray who described the book as “a national benefit, and to every man or woman who reads it, a personal kindness.” Writing about Tiny Tim, Thackeray added, “There is not a reader in England but that little creature will be a bond of union between the author and him; and he will say of Charles Dickens, ‘God Bless Him!’ What a feeling this is for a writer to inspire, and what a reward to reap!” That is praise indeed and all the more so from a fellow writer.

|

| Frontispiece to Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol, hand painted illustration by John Leech, 1843 Chapman & Hall 1st edition. From the Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham |

Not long after it was published, Dickens embarked on full readings of this favourite short novel. These readings were hugely popular and became an important revenue stream for him. Without a single prop of bit of costume Dickens peopled his stage with a throng of wonderful, colourful characters. On performance days he stuck to an unusual routine. For breakfast he had two tablespoons of rum flavoured with fresh cream. For tea a half pint of champagne and half an hour before the performance he would drink a raw egg beaten into a tumbler of sherry. During the five-minute interval, he invariably consumed a quick cup of beef tea, and always retired to bed with a bowl of soup. This unusual pre-performance ritual must have contained some alchemic quality because his readings were always incredibly popular and well received. His last such reading took place at the St. James Hall in London on March 15, 1870. At the end of the performance, he told his audience: “From these garish lights, I vanish now for evermore, with a heartfelt, grateful, respectful and affectionate farewell.” With tears streaming down his face, Dickens raised his hands to his lips in an affectionate kiss and departed from the platform for the final time. He died three months later, aged 58. Dickens name became so synonymous with Christmas that on hearing of his death a little girl asked, “Mr. Dickens dead? Then will Father Christmas die too.” Happily, the tale of Scrooge is so endearing and enduring that in spite of Dickens’ own mortality, Christmas certainly did not die, nor did his much loved A Christmas Carol.

by Stephen Darcy,

Citizens Theatre Assistant Director

Citizens Theatre Assistant Director

Image Reference: the Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham. http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/news/latest/2012/12/christmas-carol-images.aspx

A Christmas Carol takes place at the Citizens Theatre

from Sat 29 Dec 2014 - Sat 3 Jan 2015.

from Sat 29 Dec 2014 - Sat 3 Jan 2015.

Comments